Talking about the Elephant in the FTA: India, the EU and their Services Trade

India’s room for manoeuvre and the FTA’s services and investment chapter

It’s official: The Indian Prime Minister today (27 January 2026), ahead of the India-EU summit, announced the conclusion of the India-EU Free Trade Agreement negotiation, calling it a ‘perfect example of partnership’.

The stage for celebrations is set, and beautifully so. Monday’s national holiday, Republic Day, was attended by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and European Council President António Costa as Chief Guests. The elaborate staging suggests that both sides want the FTA to carry diplomatic weight – perhaps even more so as this comes barely ten days after the signing of the EU-Mercosur agreement.

The Services Elephant – does it have enough room?

While the headlines tend to focus on industrial and agricultural goods, some of the main music plays elsewhere: in the bilateral trade in services. Both India and the EU have extensive, multifaceted interests when it comes to trade in services and mutual direct investment. Both are heavy importers and exporters of services, with a lot of complementarity, so the future of bilateral services trade and investment looks bright, and the FTA is hoped to be a catalyst.

We may soon find out what solutions (or workarounds) negotiators may have found, and also which issues they may have successfully side-stepped. In any case, the constraints under which the partners operate are likely to leave their mark on the final outcome and in the reality of implementation.

Focus on India’s import perspective

Demands, of course, were raised in both directions, with India, for example, hoping for more effective access for highly qualified professionals (possibly addressed through a dedicated protocol). Our focus here is on European expectations and the likely responses from the Indian side: Where does India come from, where does it have room to move, and where may it have (had) to hold firm and resist?

What may make it into the final deal? The India-UK CETA as a proxy & benchmark

India’s most recent services commitments before this ‘mother of all deals’ were reflected in the India-United Kingdom Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (India-UK CETA), still pending ratification. A look at commitments and reservations in that agreement probably offers the best benchmark for assessing how far India may go in the deal with the EU. These can be juxtaposed with the EU’s published textual proposal for the India-EU FTA to understand India’s likely stance and, by extension, the potential direction of the final agreement.

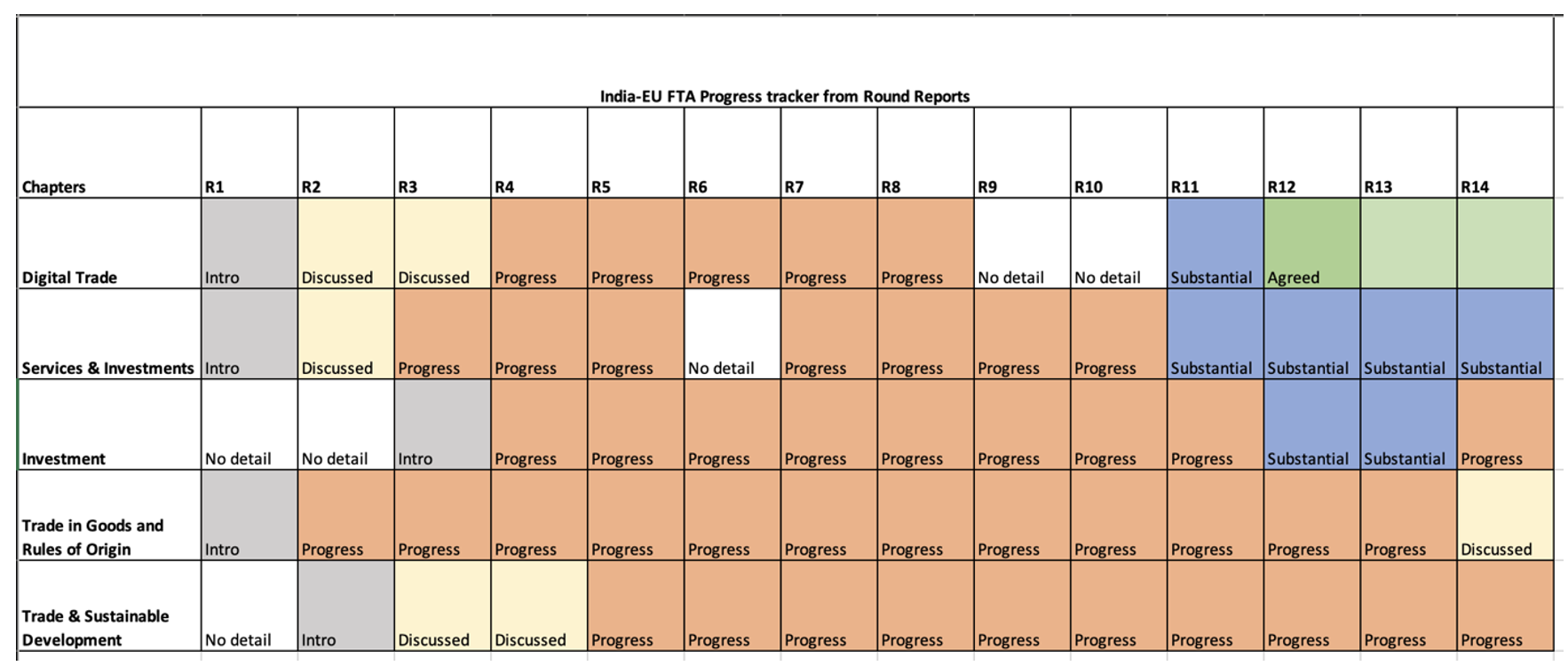

The latest rounds of negotiation usually resulted in upbeat messages regarding services – the recent “round reports” published by the European Commission describing the services and investment chapter as among the most advanced in the negotiations (while highlighting outstanding issues on market access).

So, what may be some of the sticky issues when it comes to services? What are, or were, India’s regulatory and policy choices in services that shaped its room for negotiation and/or implementation, vis-à-vis the EU’s liberal(ising) ambitions?

Source: Shilpha Narasimhan (@Shilpha_n), here’s the tracker based on the India-EU round reports, X (Twitter) as on Oct 20, 2025, https://x.com/Shilpha_n/status/1980315634748781025?s=20

Market access and local presence requirements

One area of contrasting perspectives will have been market access and local presence requirements – arguably areas of natural collision between the EU’s services ambitions and the regulatory model of India. A core tension lies in the EU’s preference for a ‘negative list’ (roughly meaning: everything is free unless specifically restricted), which would require India’s domestic regulatory structure to be mapped onto the EU’s rather liberal template.

India has so far shown little appetite for this switch vis-à-vis traditional practice. Its past FTAs, including the India-UK CETA, take the opposite approach. India follows a ‘positive list’ (as seen in Annex 8B of the India-UK CETA), where only listed sectors are liberalised. Under the India-UK CETA, like in the WTO’s GATS, any disciplines on quantitative restrictions and foreign capital limits apply only in those sectors where India has scheduled commitments, and the limitations, like the equity caps and joint venture requirements, are stated in Annex 8B. This structure allows India to open services selectively and conditionally.

The EU’s insistence on a negative list would require India to explicitly list all restrictions (aka “non-conforming measures”), effectively reversing its usual negotiating logic. This push for liberalisation challenges India’s long-standing tendency to open sectors selectively with conditions. For example, India’s Consolidated FDI Policy (2020) imposes foreign ownership caps and joint venture requirements in several industries, including telecommunications as well as financial services. These, as a minimum, would have to be listed as reservations under the negative list approach, excluding or limiting, however, the possibility of imposing similar requirements in other sectors in the future.

Under Mode 1 of services supply (cross-border services), the EU’s original proposal would prohibit requiring any local commercial presence or residency requirements. This clashes directly with India’s domestic law in services like broadcasting, banking, and insurance, where the mandatory licensing requirements are intrinsically tied to incorporating and maintaining a local entity in India. Domestic local presence requirements also extend to professional services, including legal and medical practice.

A general ban on local presence requirements would thus be difficult to reconcile with India’s current domestic regulation across a number of sectors, effectively forcing the country to reserve such sectors. That said, it seems possible that India may agree to move to more flexible, liberal rules in select service sectors, possibly on the basis of reciprocity.

National Treatment and MFN

This tension between liberalisation and regulatory design sets up the broader fault lines that are present across the negotiations, keeping observers guessing as to where exactly India’s negotiating red lines lie across the chapters.

As with market access, the EU’s proposed text (and standard approach) on national treatment (NT) is broad and applies to all sectors unless specifically excluded. India, in the context of the India-UK CETA, by contrast, limits its NT commitments to the scheduled sectors and subjects them to the conditions listed in Annex 8B of the India-UK CETA. In that agreement, for example, India scheduled the requirement to incorporate locally as a limitation on national treatment.

A similar challenge lies in an extended MFN clause, requiring the partners to extend benefits granted to third countries under preferential agreements also to each other. India has generally avoided accepting across-the-board MFN obligation which would limit its flexibility to negotiate bespoke advantages with future partners and to calibrate commitments according to domestic priorities. Instead, India so far binds MFN only in select scheduled sectors and attaches it to the “terms, limitations, conditions and qualifications” in its schedules.

For instance, in the India-UK CETA, MFN treatment applies only to the sectors in Annex 8C and clarifies that India may maintain or offer differential treatment to third countries under existing or future agreements. It also provides that the parties may consult if one party considers that a more favourable treatment has been granted to a third country after the India-UK CETA enters into force – so: an obligation to talk and engage, but no automatic extension of privileges.

Performance Requirements

Performance requirements are another area where the EU’s horizontal liberalisation model conflicts directly with India’s industrial policy framework. The EU’s demand was/is to eliminate performance requirements such as the use of local content, export quotas, domestic preference obligations, or mandates of technology transfer. Such a prohibition does not exist in the India-UK CETA.

India’s current domestic regulations necessitate such requirements. In retail services, for example, if the foreign investment exceeds 50% (for multi-brand retail trading) or 51% (for single-brand retail trading), the entity must source at least 30% of the value of goods locally, preferably from small-scale industries in the country.

Similarly, the entities (units) in the special economic zones (SEZs) receive export-performance-linked benefits. These requirements form part of India’s industrial and MSME promotion strategy, and dismantling them would face political and developmental pushback.

The EU’s demand would therefore necessitate either explicit carve-outs or transition periods for compliance, both of which India is likely to insist on.

Senior Management and Board of Directors

The EU would like to see no nationality requirements on executives, managers, or board members. However, under India’s Companies Act, 2013, at least one director must be a resident of India. This rule applies to all companies irrespective of the service they offer. As residency requirements can sometimes approximate (and hence operate de facto as) nationality requirements, a clarification that the residency requirements do not violate the clause would bring more predictability and clarity to the agreement.

Pars pro toto: A look at a few key services sectors

Telecommunications

India already meets many of the EU’s baseline asks, including the existence of an independent regulatory authority, transparency in spectrum allocation, and interconnection rights among service providers. The EU’s requests, therefore, align closely with what India has already agreed to in the India-UK CETA. This relative convergence makes telecommunications a low-friction sector in the negotiation, although India will likely continue to guard licensing discretion, while accepting transparency or regulatory cooperation provisions (telecommunication services in India currently enjoy an indefinite MFN exemption in GATS).

Transportation

Transport services, particularly maritime, are where the EU’s ambitions most directly intersect with India’s strategic and security-driven policy space. The EU seeks binding commitments preventing India from reserving certain maritime activities for Indian nationals or companies. Although cabotage is excluded, the EU clarifies that feeder services are not considered cabotage and should be open to foreign suppliers. This distinction between cabotage and feeder services is crucial because it would effectively open India’s short-haul coastal trade to EU vessels.

The EU’s proposal also includes commitments on maritime auxiliary services such as cargo handling, storage, and related logistics. Indian maritime policy, however, gives preference to Indian-flagged vessels. When foreign vessels are chartered, Indian law imposes a “first right of refusal” to Indian ships. It’s a condition also scheduled in the India-UK CETA.

Recent press reports suggest that common ground in maritime services has, in fact, been found (at least sufficiently common to allow for a political handshake now). It seems reasonable to speculate that India might (have tried to) preserve national preferences in shipping while granting openness in auxiliary maritime services.

Financial Services

Similar white smoke has emerged regarding financial services, where agreement seems to have been reached, or is close. India is likely to support many of the EU’s proposed financial services commitments, as they mirror provisions already accepted in the India-UK CETA and the GATS framework. The prudential and sector-specific exceptions align with India’s approach and are not controversial. India also supports transparency obligations such as publishing regulations, inviting comments on drafts, and maintaining clear timelines for licensing decisions.

This reflects a growing convergence on procedural transparency between India and advanced partners, even as substantive liberalisation remains carefully managed.

The EU also proposes that “new financial services” not yet present in a market may be introduced by either party’s suppliers without new legislation, subject to regulation and authorisation. This provision encourages innovation but raises concerns for India, especially in areas such as cryptocurrency and digital financial products.

Conclusion

This is an important moment for the EU and India, and arguably the rest of the world, in many more ways than one.

It is also an exciting moment for all observers of trade agreements generally and their coverage of services in particular. We will hopefully soon know what exactly the EU and India, two very different yet arguably quite complementary partners, have been able to agree on. Both have clearly acknowledged the importance of the services “elephant” in the negotiating room.

The distance between the EU’s liberalisation model and India’s sector-specific, regulatory-centric approach was and remains arguably significant. However, given the India-UK CETA precedent, India would seem comfortable to align with the EU on transparency, procedural obligations, and several elements of financial services, where convergence already exists and where India’s domestic regulatory frameworks already align with EU expectations.

However, the negative-list architecture, the EU’s original ambitions regarding the breadth of NT and MFN obligations, the proposed ban on performance requirements, and in maritime transport will likely have been met with some resistance to safeguard India’s regulatory and industrial policy space. We therefore expect to see reservations, carve-outs, and sector-specific qualifications.

The final content and also the “look and feel” of the India-EU FTA’s services chapter hinges on how far the EU is willing to match its ambitions with sector-specific flexibility, and how India may be able to design (some) liberalisation without diluting core policy instruments. In any case, it seems safe to expect that the eventual India-EU FTA will likely mirror India’s calibrated liberalisation model: deeper commitments where domestic policy already permits flexibility, and guarded positions in sectors central to India’s developmental and strategic priorities.

Navigating services and investment regulations in practice

Start with the Access2Markets database on services and investment

While trade agreements and policy initiatives can improve market access, services suppliers and investors ultimately operate within domestic regulatory frameworks that continue to shape real-world outcomes.

For EU-based firms seeking to navigate these regulatory conditions in practice, the European Commission’s Access2Markets platform offers a useful starting point. The Commission’s ‘My Trade Assistant’ for services and investment brings together information on sector-specific regulatory requirements and market-access conditions across partner countries, including India.